Researchers have uncovered a new species of pumpkin toad that is orange in color, fluorescence glow in the dark and is as small as 1 cm in size in Brazil’s Atlantic forest.

A new species of pumpkin toad has been discovered in Brazil. Researchers have uncovered a new species of pumpkin toad that is orange in color, fluorescence glow in the dark and is as small as 1 cm in size in Brazil’s Atlantic forest. This amphibian, Brachycephalus rotenbergae, is a relative of at least 36 species of pumpkin toad, named after the pumpkin popular for Halloween. Like the venom-releasing frog, the pumpkin toad’s vibrant color signals predators that their skin carries a toxin that can be lethal. This new species of pumpkin toad was recently described in the journal Plos One . They were found in extensive research efforts across Brazil to find new pumpkin toads. The identification of the organisms is crucial to the country’s biodiversity conservation, especially in areas with as many species as the Atlantic forest, where 93% of its area is lost, experts say. Initial cover due to deforestation and agricultural development.  A small pumpkin toad crawls past the bright orange mushroom, which is a common feature of their habitat. Brazil has the highest number of amphibian species in the world, at least one thousand species. But amphibians worldwide are among the most vulnerable groups of vertebrates, especially when it comes to climate change. Lead researcher Professor Ivan Sergio Nunes Silva, scientist at São Paulo State University, said: “As a scientist, the happiest moment is when you see something new and you are the only one. best know. But unfortunately, today, we are losing undetermined species faster than the rate at which new species are described. Interesting story about new toads

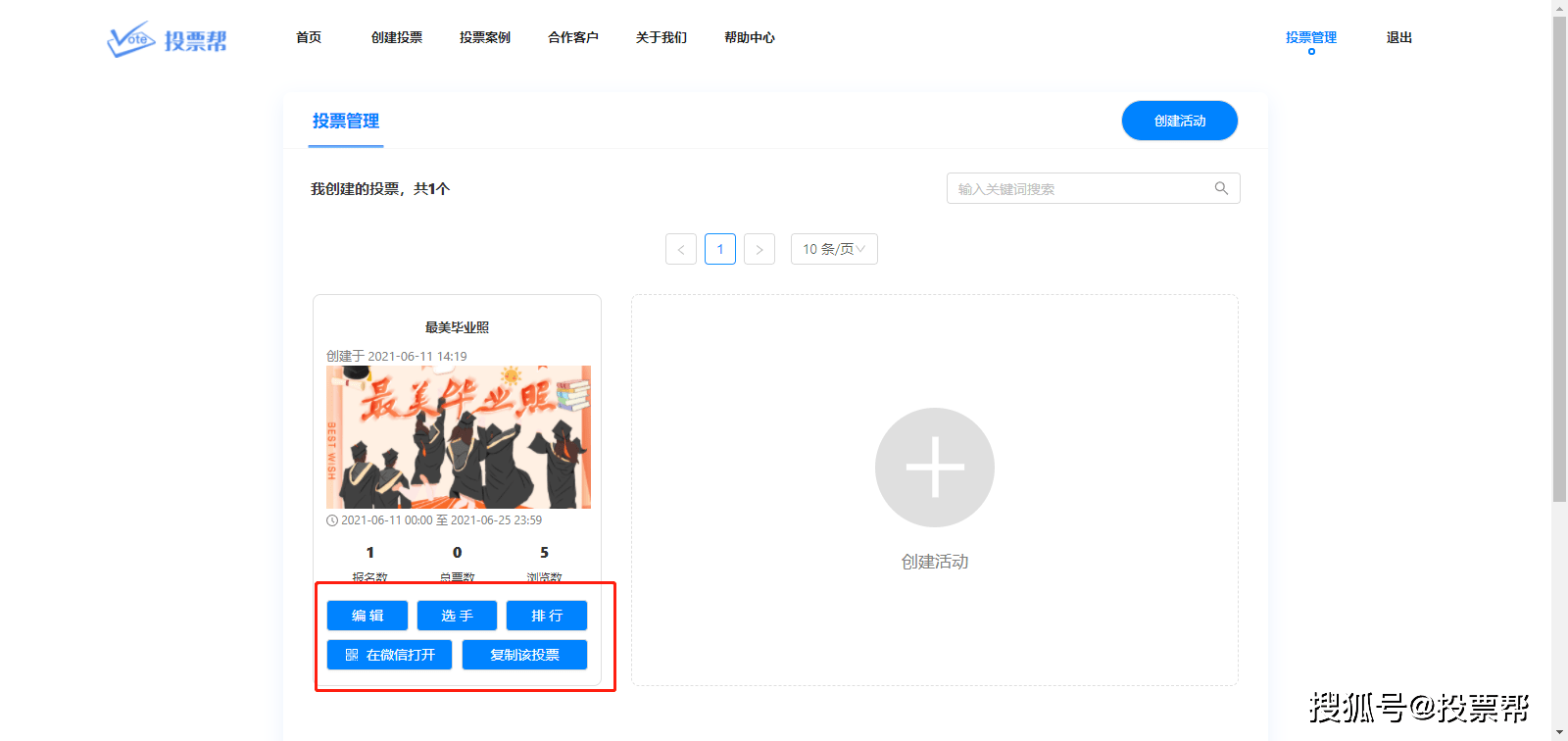

A small pumpkin toad crawls past the bright orange mushroom, which is a common feature of their habitat. Brazil has the highest number of amphibian species in the world, at least one thousand species. But amphibians worldwide are among the most vulnerable groups of vertebrates, especially when it comes to climate change. Lead researcher Professor Ivan Sergio Nunes Silva, scientist at São Paulo State University, said: “As a scientist, the happiest moment is when you see something new and you are the only one. best know. But unfortunately, today, we are losing undetermined species faster than the rate at which new species are described. Interesting story about new toads  Images of the newly discovered pumpkin toad. Photo: Plos One. Professor Nunes and his team found the pumpkin toad B. rotenbergae through 76 field surveys between 2018 and 2019 in the Mantiqueira Mountains 2,132 meters above sea level. They spent hours wandering the cliffs and streams flowing through the forest. Most pumpkin toad species are quite similar. They are particularly tiny frogs, among the smallest in the world with a length of just over a centimeter and often have bright, tangerine skin that secretes a powerful nerve agent. Back in the lab, the team took DNA samples from 71 toads and compared them with samples of known pumpkin toads. They also analyze their physical characteristics, bone structure, behavior and record their mating calls to determine that this is a new species. The new pumpkin toad, for example, is smaller than other known toads, with a smaller snout. Other unusual features include black, matte patterns on the skin and a preference for living at higher altitudes in the Atlantic forest. The creatures cannot hear the sound of their calls because their ears are not yet developed, Nunes said. “Their communication is basically visual, because these toads can communicate by opening their mouths,” he added. In particular, it is a mystery that B. rotenbergae has bone fragments on its skull and back that fluoresce and can glow through the skin under ultraviolet light, a wavelength that they can see, But humans are not. Only two other pumpkin toad species are known to emit fluorescence, Nunes added. He doesn’t know what fluorescent bones are used for, but they might play a role in communication.

Images of the newly discovered pumpkin toad. Photo: Plos One. Professor Nunes and his team found the pumpkin toad B. rotenbergae through 76 field surveys between 2018 and 2019 in the Mantiqueira Mountains 2,132 meters above sea level. They spent hours wandering the cliffs and streams flowing through the forest. Most pumpkin toad species are quite similar. They are particularly tiny frogs, among the smallest in the world with a length of just over a centimeter and often have bright, tangerine skin that secretes a powerful nerve agent. Back in the lab, the team took DNA samples from 71 toads and compared them with samples of known pumpkin toads. They also analyze their physical characteristics, bone structure, behavior and record their mating calls to determine that this is a new species. The new pumpkin toad, for example, is smaller than other known toads, with a smaller snout. Other unusual features include black, matte patterns on the skin and a preference for living at higher altitudes in the Atlantic forest. The creatures cannot hear the sound of their calls because their ears are not yet developed, Nunes said. “Their communication is basically visual, because these toads can communicate by opening their mouths,” he added. In particular, it is a mystery that B. rotenbergae has bone fragments on its skull and back that fluoresce and can glow through the skin under ultraviolet light, a wavelength that they can see, But humans are not. Only two other pumpkin toad species are known to emit fluorescence, Nunes added. He doesn’t know what fluorescent bones are used for, but they might play a role in communication.  This species has patches of bones on its skull and back that glow green through the skin under UV rays. Photo: Plos One. There is much more work to be done Professor Michel Varajao Garey, of the Latin American Institute of Natural Sciences and Life (ILACVN), said Professor Nunes and colleagues’ approach is comprehensive. Such a thorough approach could “reveal unknown diversity” and possibly reclassify some mislabeled species. In fact, up until this study, the authors say, B. rotenbergae was misclassified as B. ephippium because it looked so similar. The number of new species is unknown, but Nunes and his colleagues hope to conduct more surveys to find out where it lives, as well as look for more pumpkin toad species. Most of the rest of the Atlantic forest are protected in nature reserves, but these areas are still threatened by deforestation, climate change, and land use change. Although deforestation rates are declining in Brazil, more than 28,000 acres of forest land were cleared in 2018. Professor Nunes hopes the discovery will inspire governments and organizations to better take care of their resources, including closely monitoring endangered species. “Nature is only stable if it’s complex enough,” says Professor Nunes. This shows that biodiversity is paramount for a country as large as Brazil. “

This species has patches of bones on its skull and back that glow green through the skin under UV rays. Photo: Plos One. There is much more work to be done Professor Michel Varajao Garey, of the Latin American Institute of Natural Sciences and Life (ILACVN), said Professor Nunes and colleagues’ approach is comprehensive. Such a thorough approach could “reveal unknown diversity” and possibly reclassify some mislabeled species. In fact, up until this study, the authors say, B. rotenbergae was misclassified as B. ephippium because it looked so similar. The number of new species is unknown, but Nunes and his colleagues hope to conduct more surveys to find out where it lives, as well as look for more pumpkin toad species. Most of the rest of the Atlantic forest are protected in nature reserves, but these areas are still threatened by deforestation, climate change, and land use change. Although deforestation rates are declining in Brazil, more than 28,000 acres of forest land were cleared in 2018. Professor Nunes hopes the discovery will inspire governments and organizations to better take care of their resources, including closely monitoring endangered species. “Nature is only stable if it’s complex enough,” says Professor Nunes. This shows that biodiversity is paramount for a country as large as Brazil. “

You must log in to post a comment.