Astronauts in space for more than 6 months are likely to experience changes in eye structure. If this condition persists, their vision will be affected.

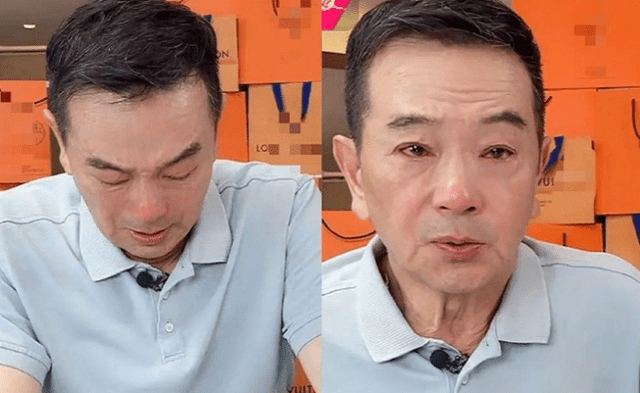

Kelly performed a spacewalk outside the space station on November 6, 2015. Time – an important “link” When humans have the opportunity to explore Mars, the crew members will carry out the mission and travel to places millions of miles away from our planet. Scientists want to understand as much as possible about the potential effects of microgravity and radiation on the human body. A big step towards this goal is the One-Year Mission, when NASA astronaut Scott Kelly and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko spent 340 days aboard the International Space Station from March 2015 to 2020. 2016. Space explorers have spent nearly a year living in zero gravity. The data collected before, during and after their flight made a big contribution. This will help researchers better understand what happens to the human body in space. One concern has arisen regarding astronauts, when their eyes change over long periods of time in space. This change is thought to occur when astronauts are in space for six months or more. Time spent in space also has potential impacts on their vision health. According to researchers, crew members typically spend four to six months on the space station. However, future planned missions lasting a year or longer should be considered. The effect on astronauts’ visual health as a result of long-term flight was previously known as visual impairment and intracranial pressure, or VIIP syndrome. The researchers are now referring to ophthalmic and neurological findings in astronauts after long-duration spaceflight, such as spaceflight-associated optic nerve syndrome, also known as SANS. A new study focusing on eye changes and problems astronauts Kelly and Kornienko experienced has been published in the journal JAMA Opthalmology. “About six months after astronauts began their space missions, we started to observe changes in the eyes of some people. Those changes didn’t show up during their roughly two-week mission aboard the space shuttle,” said study author Brandon R. Macias, director of the Cardiology and Vision Laboratory at NASA Johnson Space Center. in Houston said. According to Macias, the team’s preliminary findings suggest that the duration of the space mission could be responsible for changes in eye structure for the worse, such as swelling of nerve ending tissues. vision. This change has been noticed in some astronauts who have been on missions longer than a year in space. The premise for the future  American astronaut Scott Kelly (left) and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko (right) spent a year on the space station. The changes in astronauts Kelly and Kornienko were compared with crew members who spent about six months on the station. Both of these astronauts experienced many changes in eye structure. One of them developed mild optic disc edema. “Disc edema can occur when the nerve fibers at the back of the eye swell or when CSF (spinal fluid) builds up around the nerve fibers. If the swelling is severe and persists for a long time, visual function can be affected,” explains Macias. Meanwhile, the other astronaut suffered from optic disc edema and the growing growth of choroidal folds. Both of them used to not realize the changes they were going through. “The retina at the back of the eye is a smooth layer,” says Macias. Folds develop when this tissue becomes wrinkled and uneven. These folds can have different patterns depending on their location and severity. This condition has the potential to impair visual function.” Two astronauts recovered from optic disc edema after returning from space. However, the choroidal folds do not always fully recover. These structural changes did not result in any significant functional changes to the eye. “There is a concern, however, that longer space missions could contribute to more structural changes to the eye. The longer these structural changes take place, the more likely they are that they can cause damage to the retina,” warns Macias. The researchers believe the new findings are a reliable measurement for monitoring the crew members’ eye structures, as well as their long-term health upon their return to Earth. At the same time, the scientists also wanted to understand why some crew members had more eye changes than others. That information could help the team figure out how to prevent neuro-eye syndrome associated with space flight. The team will measure eye activity before, during and after the task by electromechanical methods. Simultaneously, the electrical response of the light-sensitive cones and rods of the eye is measured. Scientists will also look at changes in blood flow in the retina. This may provide more insight into why some crew members undergo more changes than others.

American astronaut Scott Kelly (left) and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko (right) spent a year on the space station. The changes in astronauts Kelly and Kornienko were compared with crew members who spent about six months on the station. Both of these astronauts experienced many changes in eye structure. One of them developed mild optic disc edema. “Disc edema can occur when the nerve fibers at the back of the eye swell or when CSF (spinal fluid) builds up around the nerve fibers. If the swelling is severe and persists for a long time, visual function can be affected,” explains Macias. Meanwhile, the other astronaut suffered from optic disc edema and the growing growth of choroidal folds. Both of them used to not realize the changes they were going through. “The retina at the back of the eye is a smooth layer,” says Macias. Folds develop when this tissue becomes wrinkled and uneven. These folds can have different patterns depending on their location and severity. This condition has the potential to impair visual function.” Two astronauts recovered from optic disc edema after returning from space. However, the choroidal folds do not always fully recover. These structural changes did not result in any significant functional changes to the eye. “There is a concern, however, that longer space missions could contribute to more structural changes to the eye. The longer these structural changes take place, the more likely they are that they can cause damage to the retina,” warns Macias. The researchers believe the new findings are a reliable measurement for monitoring the crew members’ eye structures, as well as their long-term health upon their return to Earth. At the same time, the scientists also wanted to understand why some crew members had more eye changes than others. That information could help the team figure out how to prevent neuro-eye syndrome associated with space flight. The team will measure eye activity before, during and after the task by electromechanical methods. Simultaneously, the electrical response of the light-sensitive cones and rods of the eye is measured. Scientists will also look at changes in blood flow in the retina. This may provide more insight into why some crew members undergo more changes than others.

You must log in to post a comment.