In Turkey, many people have lost their jobs, government support is scarce: The corona crisis is particularly hard on the numerous unregistered workers.

Karin Senz, ARD studio Istanbul There’s a lot going on in the large square in front of Istanbul’s Bazaar district, but not nearly as much as before the pandemic: a few Arab tourists and locals stock up on their fasts or just sit in the sun. Ali stands at his little oil press and waits in vain for customers. He usually works seven days a week and gets around 3,000 lira, that’s a little more than 300 euros. With that he can just make ends meet. But now it’s lockdown on the weekend. “That’s why I only work five days a week and get 100 lira a day, which makes about 2000 lira a month,” says Ali. “That’s not enough to support my family. But what should I do? We have all got used to these circumstances.”

No protection from state social security

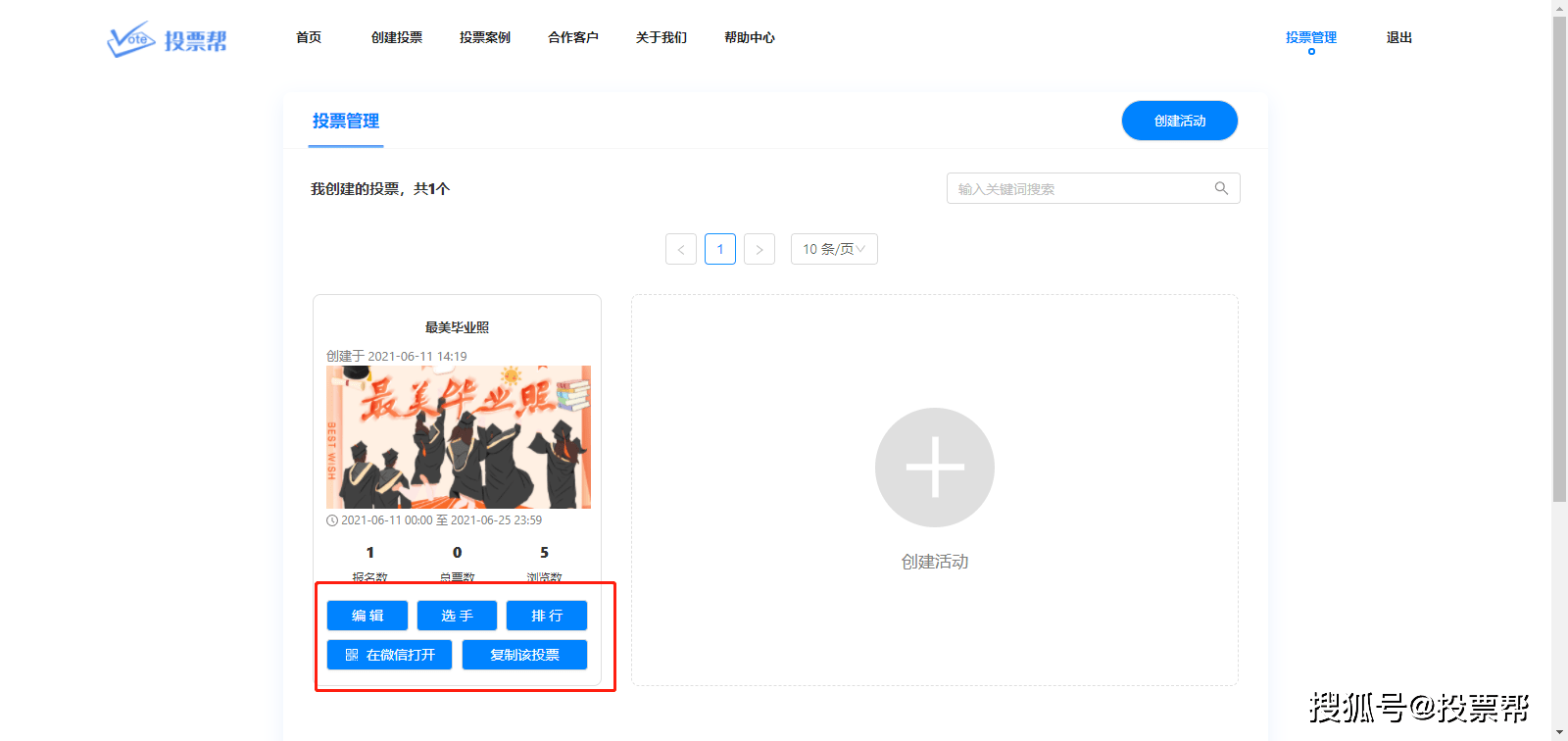

He does not get compensation from the state, which ordered the lockdown. “In Turkey it is very common that you do not work in small companies, for example in restaurants, small hotels or workshops,” says Istanbul economist Baris Soydan. An estimated 30 percent of workers are not registered – and thus without social and unemployment insurance, like Ali. The Turkish media reported that around 2.5 million permanent workers were sent on unpaid leave by their bosses. The state pays them around 1000 lira a month, a good 100 euros. Mücke is sitting a few doors down behind the counter in her little shop. It’s full of Turkish sweets – but not a single customer can be seen. “Before the pandemic, we had two shops, one more straight down the street,” she says. “We had to close it, the shutters are down. At the moment we’re trying to stay afloat with this shop.”

Terminations despite the ban

The 40-year-old could have applied for a rent subsidy, around 100 euros. But that wouldn’t matter with the high rent she has to pay here in the tourist district, she says. That is why she did not even apply for the grant: “We get state support for the insurance contributions of the employees. And there are reductions and deferrals for income tax. But that’s it.” Mücke has five employees. She has not cut their salaries, she says – although the working hours are significantly shorter from the early evening due to the weekend lockdown and curfews. “We were able to claim short-time work allowance for two months. It was said that it would be extended to June. But then they ended it. That is over.” Actually, the state has banned firing workers during the pandemic. According to the Turkish statistical office, around 250,000 people lost their jobs in February alone.

No rate cut

Turkey only went into a complete lockdown a year ago, which then lasted almost three months. Since then, the shops have remained largely open. Restaurants, cafes and bars are closed from time to time, as they are now during Ramadan. “Last year, in 2020, the economy in Turkey grew by 1.8 percent. In Germany, for example, it shrank,” says economic expert Soydan. “From a purely macroeconomic perspective, things went okay here, but not for the population.” Inflation is currently over 16 percent. That is also why many Turks looked to the decision of the new head of the central bank, Sahap Kavcioglou, on Thursday. The central bank did not comply with President Erdogan’s request to lower the key interest rate. Expert Soydan warns of another sticking point: the upcoming holiday season. “It could be that this year there are not many tourists from Germany or Russia,” he says. “If that were the case, significantly fewer foreign currencies – that is, euros and dollars – would enter Turkey.” And this is what the country needs – especially now in the pandemic. And the waiters, maids, bartenders, and entertainment staff need the jobs. At the moment, however, Turkey is struggling with record levels of around 60,000 new infections per day. Many people find it difficult to think of a successful holiday season.

You must log in to post a comment.