They are volunteers – all young and healthy – carefully selected to be infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus for research purposes.

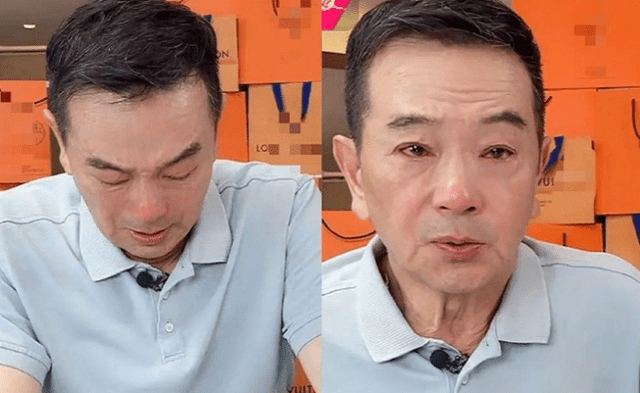

Jacob Hopkins, the first volunteer directly infected with the virus These volunteers have lined up to participate in the “human trial,” which has long been successfully used to develop vaccines for diseases such as typhoid and cholera. The world’s first human trial for Covid-19 began in the UK in March of this year, as scientists tried to determine the minimum dose of virus needed to infect volunteers. from 18 to 30 years old.  Alastair Fraser-Urquhart, human trial volunteer Alastair Fraser-Urquhart “registered immediately” to participate in the trial and also became the manager of 1Day Sooner, a British non-profit that advocates for volunteers to participate in research studies. save on humans. “We are really, really lucky that an mRNA vaccine is a viable platform to start with, but there is no guarantee it will,” he said, “And even if it turns out to be completely useless. , thanks to a test like this, you can detect that in a matter of weeks instead of months.” Mr Fraser-Urquhart was one of the few to take part in the first phase of the trial, in which volunteers were screened before going into isolation at the Royal Free hospital in London. A few days later, the virus was injected into Fraser-Urquhart’s nose by a scientist wearing full protective gear while he lay in bed wearing only a T-shirt and jeans. There were about six other researchers, all covered from head to toe, standing in that room. “One of them stood in the corner of the room and counted down the seconds… as if it were a rocket launch,” Fraser-Urquhart said. He said the experience was both terrifying and memorable. “In the same room with such a large amount of pure virus… it looks like normal water. I didn’t expect to see coronavirus like this.” According to Jacob Hopkins, the first volunteer directly infected with the virus, after being injected, they will lie down for 10 minutes before sitting up and holding the position for another 20 minutes. “When we finished, we were… high five. It was a really weird moment, it was like “that’s great, Covid!”? And then it all really started.” After contracting the virus, the participants were monitored 24 hours a day for at least 14 days, and blood samples and nasal swabs were collected every day. Both Fraser-Urquhart and Hopkins felt fine for the first few days, but had to go through a few “difficult” days before recovering. “Honestly, it wasn’t easy, but it was an extraordinary experience, and one of the best things I’ve ever done in my life,” Hopkins said. “When you contribute to a project that can bring a lot of good… it feels good to be a part of it.” After discharge, the participants were followed up for a year so the researchers could detect any long-term symptoms. Overall, each person will be supported around £4,500 (VND 146.8 million) for their contribution. Fraser-Urquhart donated his first donation to The Vaccine Alliance, and plans to donate the rest to other charities. “It’s good to be able to demonstrate that at least some of the volunteers participate purely out of compassion,” he said. “Actually, this support never influenced my decision to join.” Some scientists have hesitated to expose volunteers to Sars-CoV-2 – the virus behind COVID-19 – because it currently has no cure, although there are several methods. The treatment has been shown to be effective. Meanwhile, some advocates of the trial argue that the coronavirus poses a low risk to young and healthy people and offers high benefits to society. These benefits include the ability to accelerate the development of a second-generation vaccine, as developing countries grapple with inadequate demand. They can also be used to compare people who are suitable for vaccines, develop treatments, and advance the scientific understanding of the virus.

Alastair Fraser-Urquhart, human trial volunteer Alastair Fraser-Urquhart “registered immediately” to participate in the trial and also became the manager of 1Day Sooner, a British non-profit that advocates for volunteers to participate in research studies. save on humans. “We are really, really lucky that an mRNA vaccine is a viable platform to start with, but there is no guarantee it will,” he said, “And even if it turns out to be completely useless. , thanks to a test like this, you can detect that in a matter of weeks instead of months.” Mr Fraser-Urquhart was one of the few to take part in the first phase of the trial, in which volunteers were screened before going into isolation at the Royal Free hospital in London. A few days later, the virus was injected into Fraser-Urquhart’s nose by a scientist wearing full protective gear while he lay in bed wearing only a T-shirt and jeans. There were about six other researchers, all covered from head to toe, standing in that room. “One of them stood in the corner of the room and counted down the seconds… as if it were a rocket launch,” Fraser-Urquhart said. He said the experience was both terrifying and memorable. “In the same room with such a large amount of pure virus… it looks like normal water. I didn’t expect to see coronavirus like this.” According to Jacob Hopkins, the first volunteer directly infected with the virus, after being injected, they will lie down for 10 minutes before sitting up and holding the position for another 20 minutes. “When we finished, we were… high five. It was a really weird moment, it was like “that’s great, Covid!”? And then it all really started.” After contracting the virus, the participants were monitored 24 hours a day for at least 14 days, and blood samples and nasal swabs were collected every day. Both Fraser-Urquhart and Hopkins felt fine for the first few days, but had to go through a few “difficult” days before recovering. “Honestly, it wasn’t easy, but it was an extraordinary experience, and one of the best things I’ve ever done in my life,” Hopkins said. “When you contribute to a project that can bring a lot of good… it feels good to be a part of it.” After discharge, the participants were followed up for a year so the researchers could detect any long-term symptoms. Overall, each person will be supported around £4,500 (VND 146.8 million) for their contribution. Fraser-Urquhart donated his first donation to The Vaccine Alliance, and plans to donate the rest to other charities. “It’s good to be able to demonstrate that at least some of the volunteers participate purely out of compassion,” he said. “Actually, this support never influenced my decision to join.” Some scientists have hesitated to expose volunteers to Sars-CoV-2 – the virus behind COVID-19 – because it currently has no cure, although there are several methods. The treatment has been shown to be effective. Meanwhile, some advocates of the trial argue that the coronavirus poses a low risk to young and healthy people and offers high benefits to society. These benefits include the ability to accelerate the development of a second-generation vaccine, as developing countries grapple with inadequate demand. They can also be used to compare people who are suitable for vaccines, develop treatments, and advance the scientific understanding of the virus.

You must log in to post a comment.